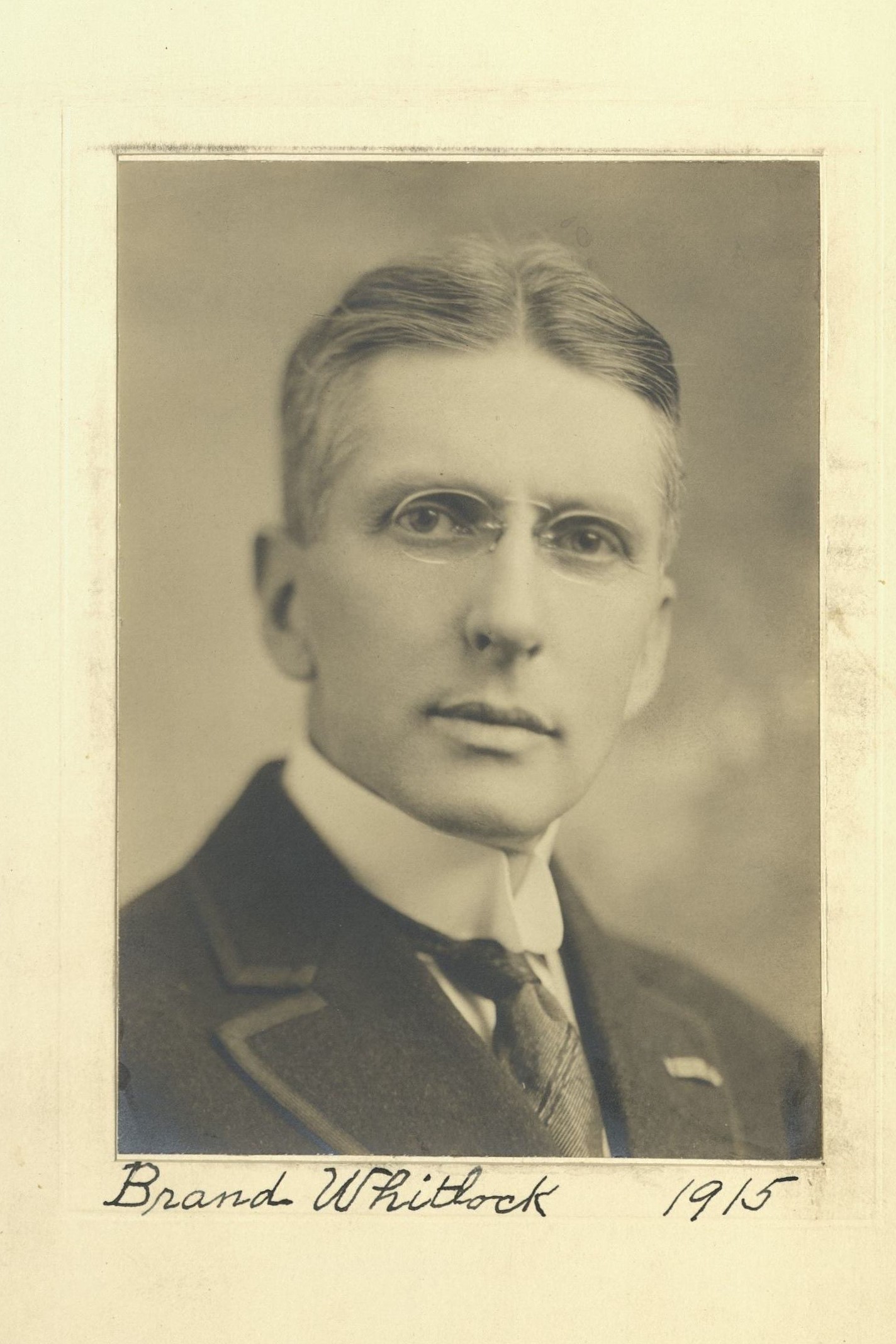

Minister to Belgium/Journalist/Author/Mayor of Toledo

Centurion, 1915–1934

Born 4 March 1869 in Urbana, Ohio

Died 24 May 1934 in Cannes, France

Buried Cimetière du Grand Jas de Cannes , Cannes, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, France

, Cannes, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, France

Proposed by Arnold W. Brunner and William Dean Howells

Elected 4 December 1915 at age forty-six

Century Memorial

When President Wilson selected in 1913 his foreign ministers and ambassadors, he constantly applied the familiar American criterion of literary distinction. Thomas Nelson Page went to Rome. At the Court of St. James’s, Walter Page revived traditions of Lowell’s time. For the smaller diplomatic post of Brussels, Brand Whitlock was designated. With all of these appointments the President evidently had in mind, not only representation of America abroad by Americans of culture, but the chance for descriptive writers to enlarge their own horizon through contact with the greater world, an opportunity for their leisurely pursuit of literary activities.

Whitlock had not been exclusively a writer. At the age of thirty-six, when the wave of municipal reform swept over his native state, he had plunged into politics, had been elected and three times re-elected Mayor of Toledo. But human interest of the literary sort pervaded even these political activities. While installed in the City Hall, Whitlock wrote two or three of the dozen novels which bear his name; one of his published stories of that period was frankly based on Toledo city politics. He confessed, when accepting the Belgian post in 1913, his expectation of completing in that quiet diplomatic atmosphere another novel dealing with small-town Ohio life. He was not alone in such anticipations. As late as May of 1914, the German Minister at Brussels remarked to Whitlock that, although he himself had “never had a post where there has not been trouble” and although, diplomatically speaking, he had hitherto been “a bird of ill omen,” now he had been transferred to “the most tranquil post in Europe.” “Nothing can happen at Brussels,” he concluded. But Whitlock’s novel, begun in 1913, was not destined to be in a publisher’s hands until 1923.

Whitlock’s was an imaginative mind; in his stories he was fond of creating wholly unexpected situations. Yet the uttermost stretch of his creative imagination would not have suggested beforehand the possibility that in August, 1914, the eyes of all the world would be on the United States Minister to Belgium; that his name, like those of Cardinal Mercier and Food Administrator Hoover, would presently divide international interest with the names of Joffre, Hindenburg and the German Kaiser; that his appeal to a stubborn German military satrap in behalf of the English nurse Cavell would cause a simultaneous throb of emotion from St. Petersburg to San Francisco. Such were the amazing turns of circumstance, in that portentous episode of human history.

The story of Whitlock’s own activities during the German occupation is too well known to need repetition. What the Belgian people thought of them was sufficiently indicated through their conferring on him the rare distinction of “honorary citizen” of Brussels, Antwerp, Liège and Ghent, through formal recognition of his services by special vote of the Belgian Senate in extraordinary session, through the naming for him of a boulevard in Brussels and through the placing of his bust in the Belgian Senate-chamber. Whitlock has set down frankly and categorically, in the only book written during his official tenure, the account of what he saw of the German occupation, what he knew, and what he learned on first authority. Although the narrative is as far removed as the task made possible from bitterness or rancor, it is painful reading. But its faithful and dispassionate citation of documents, proclamations, and events of public knowledge will possibly serve hereafter as antidote for the teachings of self-created apologists outside of Germany, who, because rumor had manifestly exaggerated some of the German cruelties in Belgium, reject all accounts of military barbarity, picturing invasion and occupation as the natural act of a generous government, driven to defend itself against Belgian defiance and the unprovoked aggression of its neighbor states.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1935 Century Association Yearbook