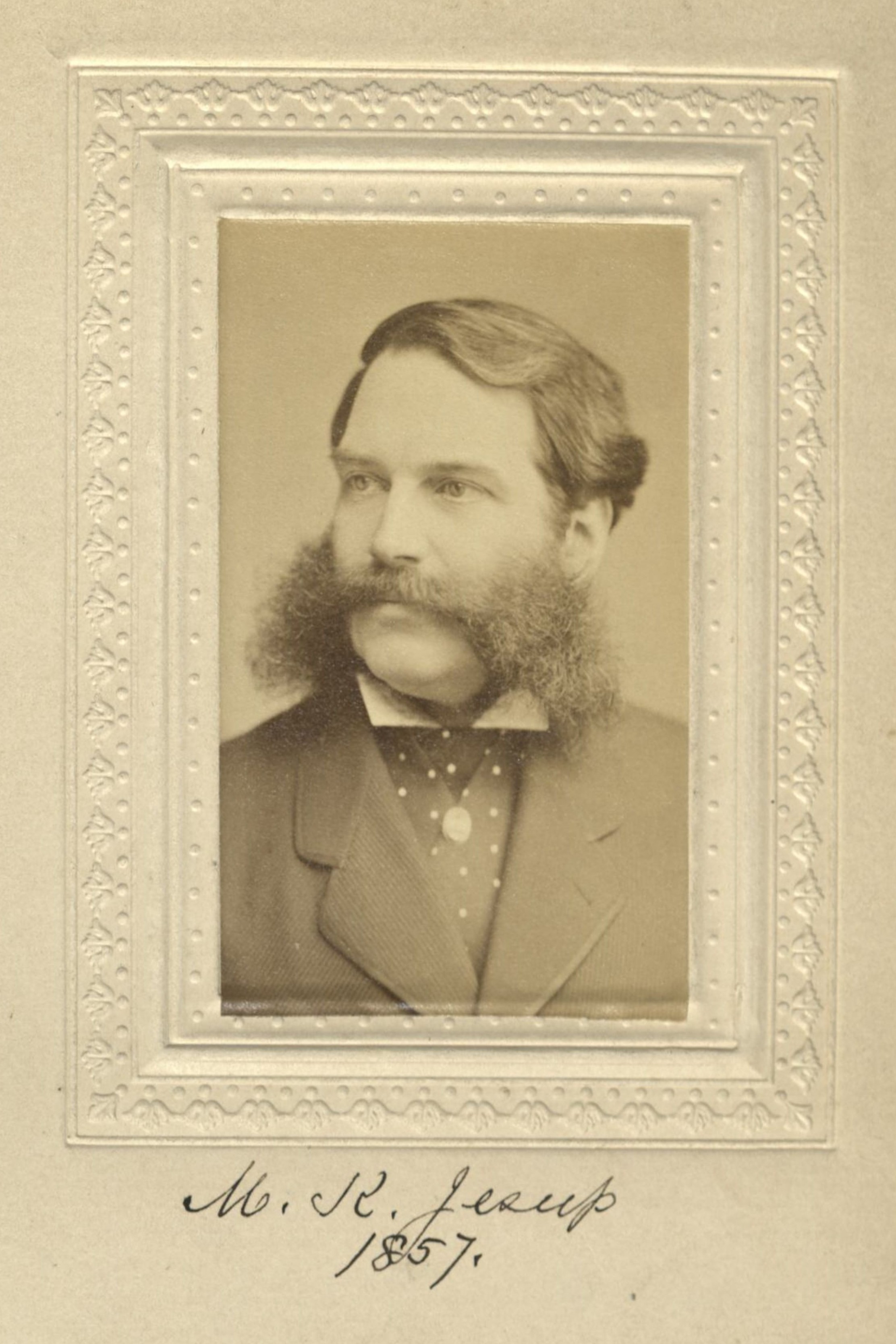

Banker/Philanthropist

Centurion, 1857–1908

Born 21 June 1830 in Westport, Connecticut

Died 22 January 1908 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Peter Marié

Elected 5 December 1857 at age twenty-seven

Archivist’s Note: Cousin of J. R. Jesup

Seconder of:

Supporter of:

Century Memorial

Morris Ketchum Jesup was born to the affluence of noble aspirations, but, orphaned at twelve, he inherited little else. With a sound school training and scarcely more than an introduction to college, he entered the stern conflict of business life when a mere boy. Such was the sterling metal of his character that at twenty-two he established an independent firm in New York. His inborn sympathy for spiritual pursuits and his rich endowment of companionable qualities made him a member of The Century at twenty-seven. For fifty-one years he was part of the living organism which keeps us ever young, ever creative, ever sensitive to our responsibilities. In the end, his education was thorough, comprehensive, vitalizing; and, as he was prospered beyond his visions, he showered on the community, with bewildering generosity, the benefits he had received, giving himself, with his wealth, to enterprises which have gone far to regenerate the life of New York, to place science on a new foundation, and to spread in all lands the gospel of Jesus Christ, whose humble servant he considered himself in every activity of his life.

He was a banker, a director of enormous corporations in the interests of their stockholders, prominent in the Chamber of Commerce, and its President for many years. The business honor of his adopted city was closer to his heart than any other secular interest: under all circumstances he pleaded for it, safeguarded it, and was continually selected to represent it. Though he retired from active business at fifty-four and thereafter for a quarter of a century devoted his splendid powers chiefly to other service, yet he maintained a commanding position in the industrial and commercial world to the very end.

Mr. Jesup was a devoted churchman in the denomination to which he belonged, being firmly convinced that philanthropy without faith was like a tree with no tap-root. He was a church member who found his highest duty in the most generous support of church enterprises for the spread of its domestic and foreign influence, and in close connection with the organic life of the congregation with which he worshipped. But these intimate relations were only a starting-point and a foundation for his wider activities. He was a founder of the Young Men’s Christian Association, he gave to the Children’s Aid Society an important building, was President of the Five Points House of Industry, of the American Sunday School Union, of the New York City Mission and Tract Society, an officer of the United States Christian Commission during the Civil War, of the Union Theological Seminary, and of the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut, that wonderful English-speaking university which, with Robert College, has contributed so mightily to the regeneration of the hither East. He was a princely benefactor of all these; to them, singly and collectively, he gave unceasing, loving care, more energy and thought probably than to his business enterprises.

As in the Christian, so in the secular world, education was his chiefest care. He gave liberally to Williams, to Yale, and to Princeton. He exerted himself powerfully in the cause of forest preservation and in the husbanding of all our national resources; expeditions which were supported by him carried his name to both ends of this continent, almost from pole to pole, and in geology, palæontology, biology, and ethnology enriched our scientific apparatus to the admiration and envy of distant and older lands. The Czar of Russia made him a companion of the highest Russian order for scientific service to that country. King Edward received him with respect as head of a commission laboring in the interests of humanity and peace. He was a discriminating collector of books and pictures, an officer of our three most important art societies.

But, while toiling ceaselessly in all these interests, he knew how to concentrate his highest powers in one. For his work, first as an organizer of the Natural History Museum, and later as its President, four universities gave him academic recognition, one of them its highest honorary degree. To this great educational enterprise in the city of New York no other is second, for it stands in the front rank: first for popular education, second for its scientific collections, and thirdly as a hearthstone of original research. The spacious buildings erected by the community are filled to overflowing with collections of prime importance, its staff of workers are men of the highest standing in the scientific world, and its publications are standard authorities. Others have contributed lavishly to this triumph of private enterprise, but no one to the same degree as Mr. Jesup. His benefactions have been far the largest, his energies have been the most devoted, his organizing powers have been, with no detraction from the merits of others, the most efficient, and his bequests have enabled it to take another great step forward. With its grandeur his name is inseparably linked.

Not one of us has forgotten the presence of the man: his fine form, his stately bearing, his serene and earnest countenance. He was often with us and his discourse was generally of high things; though he could at times unbend and lend himself to mirthful talk. Yet in the main there was in him a sense of high calling. He was a convinced and tenacious optimist, sure that the Kingdom was coming, even on earth, and that it was a man’s work to help it forward. He lived long and noted the steady uplift of New York life. He was never confused by the lapses which so engage the attention of less constructive minds. I have heard thoughtless and contemptuous abuse of this city meet with scathing rebuke at his hands. Expansion was the experience of his personal life, it was his creed for religion and education and patriotism. Of a stock that had been American for the greater part of three centuries, he saw the perspective of centuries yet to come in the light of hope and faith.

William Milligan Sloane

1909 Century Association Yearbook