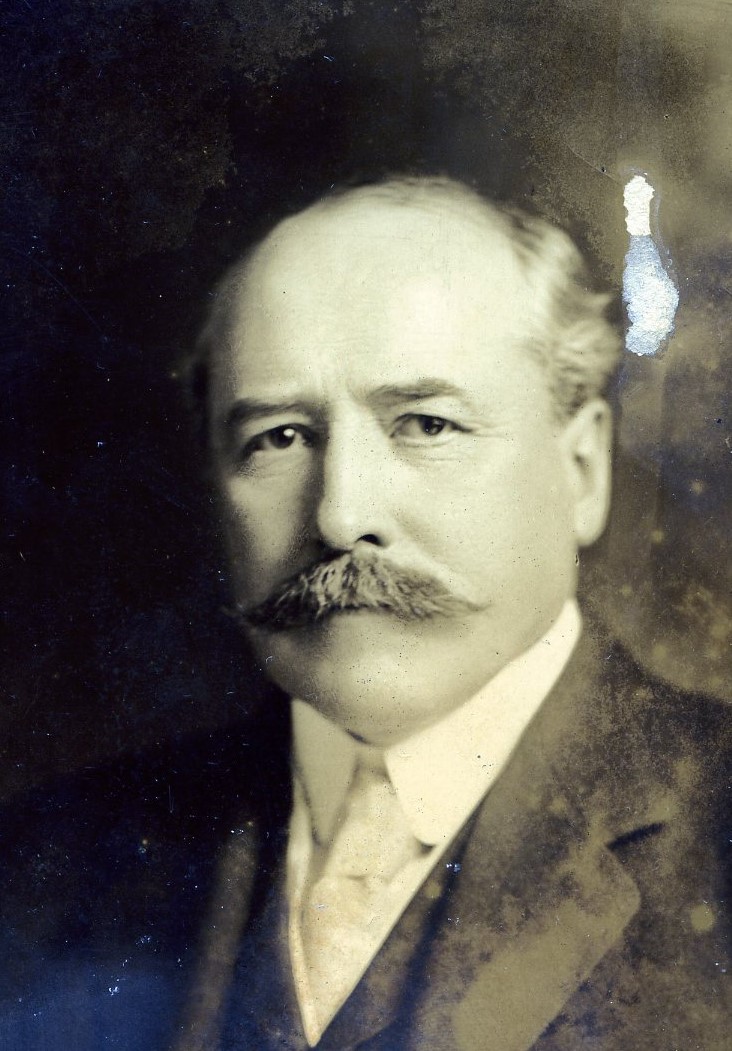

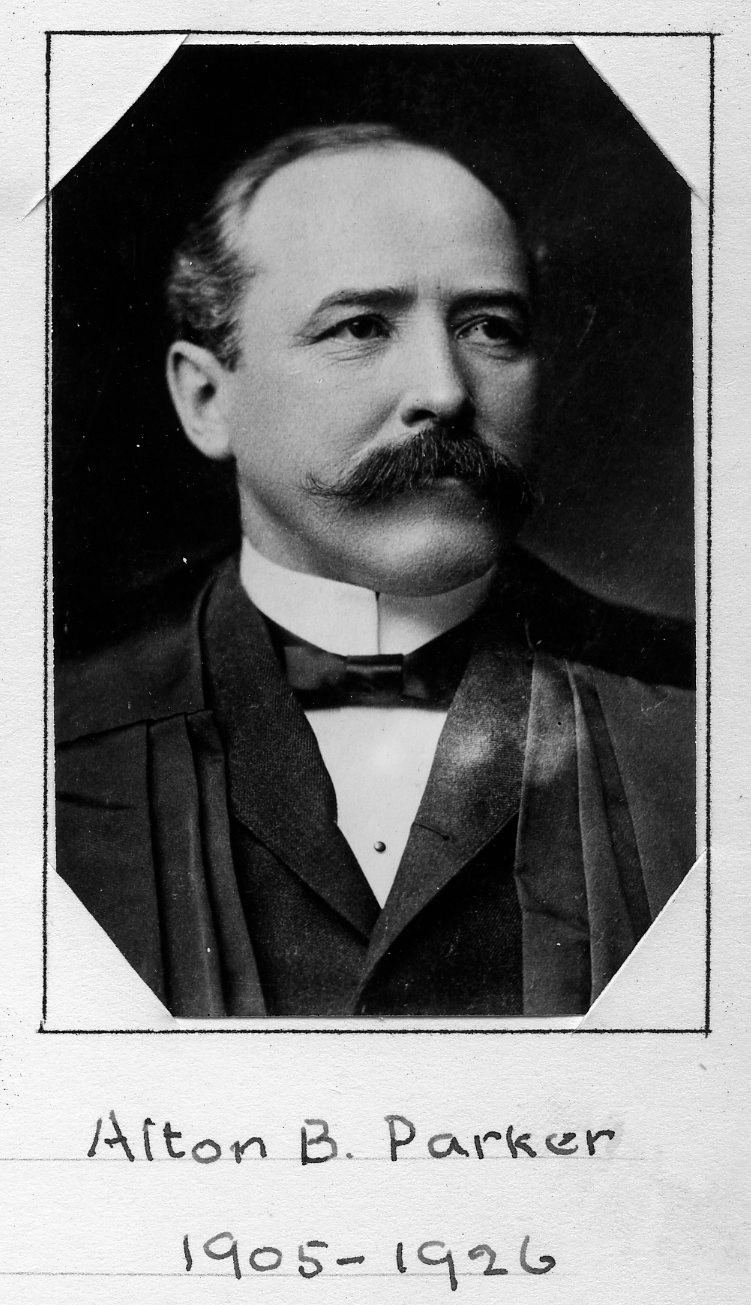

Lawyer

Centurion, 1905–1926

Born 14 May 1852 in Cortland, New York

Died 10 May 1926 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Wiltwyck Cemetery , Kingston, New York

, Kingston, New York

Proposed by Edward Patterson and Charles R. Miller

Elected 1 April 1905 at age fifty-two

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

The career of Alton Brooks Parker illustrates two facts regarding American public life that are not always recognized. One is that, on the whole, the public man is fortunate whose memory is associated with a single notable action applauded by every one, rather than with many achievements of disputed merit; the other, that a candidate for office may sometimes win more distinction in defeat than another would have won in victory. We have lived through so much checkered political history since the end of the Nineteenth Century that it is not so easy nowadays for the general public to recall the period in which one of our two great parties seemed to have tied itself up hopelessly with the issue of free silver coinage and depreciated money. Bryan had twice led the Democratic party to disastrous defeat on the silver platform, yet in 1904 he still seemed to dominate the party’s councils. He could hardly himself aspire to be its presidential candidate for the third successive time, but he undertook to dictate its platform. Confronted with stubborn opposition to repetition of the politically ruinous “silver plank,” he laid down the ultimatum that at least there should be no repudiation of that doctrine and the convention, meekly and unanimously, took the course of adopting a platform with no mention whatever of the money standard.

When it came to the presidential candidate, the convention’s choice was governed by the fact that, whereas the pivotal New York State had polled against Bryan pluralities of 143,000 in 1900 and of 268,000 in 1896, Parker in 1897, in the vote for Chief Justice of the Appellate Court, had carried the State on the Democratic ticket by 60,000. Bryan fought his nomination at Chicago bitterly, protesting against consideration of a man for the country’s highest office “on the ground that his opinions are unknown.” He soon had opportunity to learn them. The convention’s nomination of Judge Parker on its platform of evasion was instantly followed by the famous telegram from the candidate, stating that he himself regarded the gold standard as “firmly and irrevocably established” and would act accordingly if elected. He did not stop with that. The candidate’s own opinion was now known to all the world, but the opinion of the convention and of the platform still fitted Bryan’s description. Judge Parker’s telegram therefore further instructed his friends at Chicago, in case his attitude towards the money standard “proved to be unsatisfactory to the majority,” to “decline the nomination for me at once.” When the convention thereupon humbly voted, 4 to 1, that it wished him to remain on his own sound-money platform, free silver coinage as an issue in American politics was dead.

The courage of the action drew strong commendation (privately expressed, however,) from no less a person than his opponent for the presidency, Mr. Roosevelt. Both Parker and Roosevelt knew that this defiance to the revengeful Bryan faction gravely prejudiced the candidate’s prospect of success. Nowadays, in retrospect, it looks as if Parker never had a chance of victory; but it did not seem so in July of 1904. Before the telegram was sent it was believed that, between internal quarrels in the Republican party, sweeping reaction in trade and resentment of “big business” over the “Roosevelt policies,” the chances for election day were fairly balanced. The November vote swept the country for Parker’s opponent, but the high moral distinction of the Democratic candidate’s action in July was, if anything, enhanced by that result.

Judge Parker’s genial spirit and abounding vitality made their mark in social and professional circles, before and after 1904. Not perhaps a profound lawyer, he was a very useful judge, a sound adviser and a citizen whose great kindliness and unassuming manner brought him hosts of friends.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1927 Century Association Yearbook