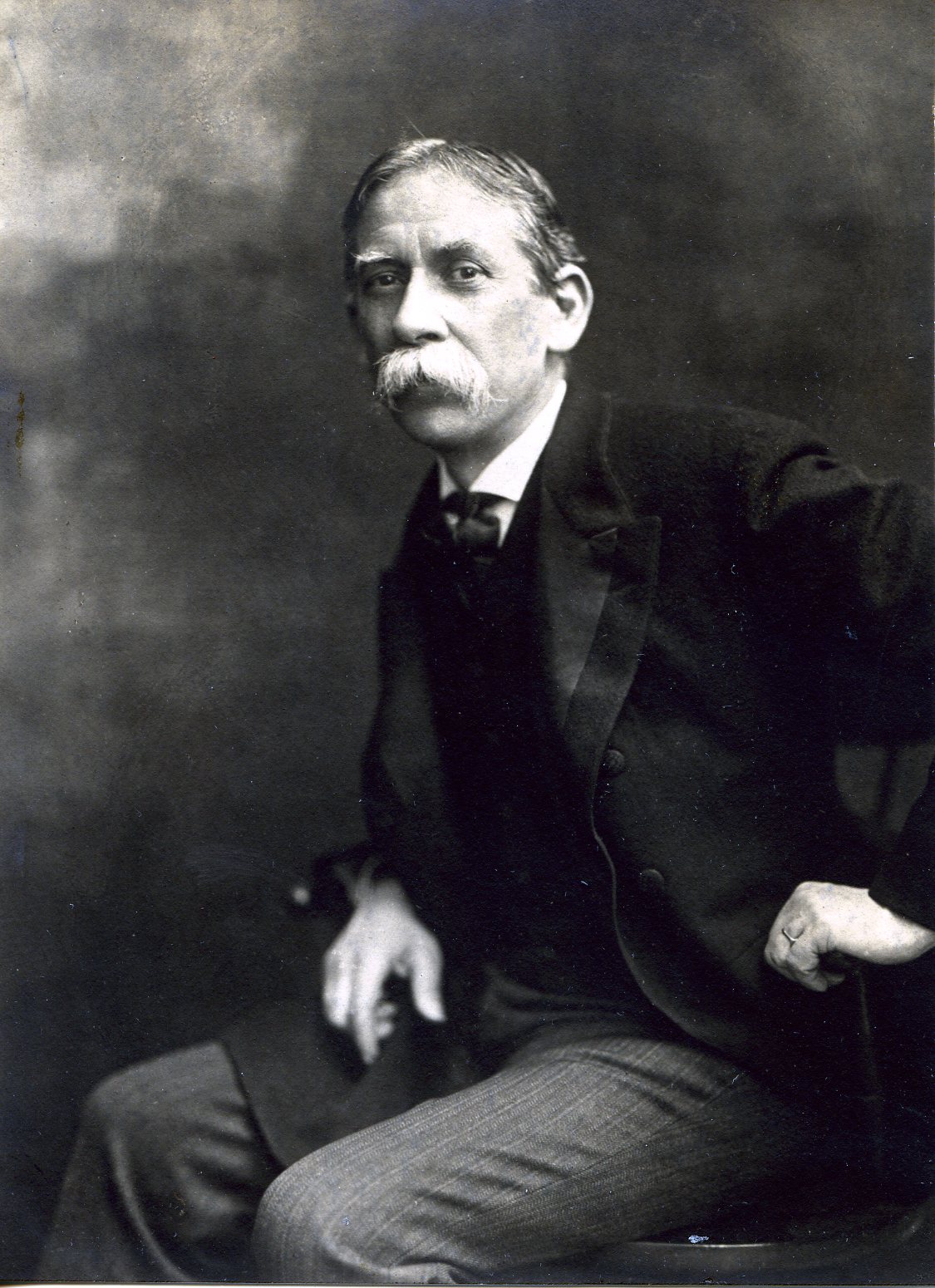

Editor

Centurion, 1913–1928

Born 20 July 1849 in Aabey, Lebanon

Died 24 January 1928 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Utica, New York

Proposed by Hamilton W. Mabie and William Crary Brownell

Elected 1 February 1913 at age sixty-three

Century Memorial

If there are men whose ideas, mannerism and personality are the embodiment of their craft, Talcott Williams was one of them. The kindling of interest in his face when a controverted matter entered the discussion, the searching glance from behind his high-power glasses, the incisive and oracular statement of opinion, were in their way the incarnation of journalism. There were in fact few highroads or bypaths in the newspaper profession that Williams had not explored. He had interviewed sporting celebrities on “space assignment,” had edited copy at the night desk with a green shade on his forehead and a cup of coffee at his elbow, chased down the petty political intrigue of Albany, tramped from the Capitol to the Treasury and from the Treasury to the White House on the track of those rumors that rise from the ground at Washington, prescribed the attitude of city newspapers on questions of the day and dashed off their leading editorials. Into each successive field of journalistic achievement he brought the same enthusiasm. Nothing escaped his penetrating observation, and when, at the ripe age of 62, he was summoned to put the New York School of Journalism into action, he probably knew as much of the practical details of his craft as any living man.

Williams had rare power of imparting this knowledge to the neophyte; who may well, however, sometimes have been dismayed at his teacher’s offhand description of what an ordinarily capable newspaper man should be prepared to do. That functionary ought, the preceptor told his pupils, to “give a good abstract of a newspaper column of leaded nonpareil in ninety seconds,” to submit in twenty minutes “a fair outline of a sixteen-page newspaper—foreign and local news, the market, editorial page, special stories and criticism,” or to turn out 2,000 words of “clean copy” in an hour. Even to seasoned journalists this is a counsel of perfection. But Williams had calculated by his own habitual performance at the desk, where it is easy to imagine that piercing eye, which nothing escaped, devouring the proof-sheets at 1 A.M.

Williams had more to tell, however, than the routine of the journalistic task. He had passed through all its stages with a philosophic mind and a keenly observant eye. Of the cynic, in or out of the newspaper world, who finds that “nobody reads the editorials,” he blandly asked “how it happens,” then, that “nothing cuts into the circulation like an editorial blunder.” Musical or dramatic criticism was outside his sphere of personal activity but not outside his sphere of observation; he has a mildly contemptuous word for the critic who insists on telling his readers “what a presentation is not, instead of what it is.” Like most philosophers, his views were not always consistent. That the newspaper ever does anything for real literature he expressed emphatic doubt; which, however, did not prevent him from asserting on another occasion that “there is much literature, and some very good literature, in journalism; much journalism, and some very bad journalism, in literature.” Again like other philosophers, he had his hobbies. “Leader writers would have written in a literary tongue if Johnson had had his way,” Williams insisted, “but Benjamin Franklin saved us”—a verdict flattering to patriotic pride, but hardly just to Swift and De Foe [Defoe], or even to those pseudo-Parliamentary debates in which the Doctor himself was careful never to let the Whig dogs get the best of it. But the real point was that Williams cordially disliked that not infrequent editorial writing whose ponderous formality conceals unfamiliarity with the subject; in addition to which, he insisted on the right of the press to talk the plain man’s language. He knew that this was slippery ground, with Hearst and the tabloids appropriating the dialect of messenger boys and shop-girls. But when a well-known newspaper was rebuked for saying of a blundering public character that he “got what was coming to him,” Williams pronounced it perfectly good newspaper English. He even defended a fellow-writer for describing an opponent’s argument as “bunk”—though in that case warily (and, one may hope, prophetically) admitting that the future “might discountenance the word.”

A man with such background as Williams had was not likely, when called to conduct the School of Journalism, to applaud the very prevalent notion that a “course” in reporting, writing, editing and criticizing would turn out a full-blown journalist. He told his pupils that two years of preparation, three of college and three of technical work would possibly do that, but that the training would not go for much unless supplemented by American and European history, economics and political science. This was a program to shake the composure of young gentlemen who offer their services to edit metropolitan dailies a week or two after Commencement, but it reflected the ideals of a practical journalist who knew his own profession thoroughly and was proud of it.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1929 Century Association Yearbook