Professor of History

Centurion, 1915–1928

Born 6 March 1866 in Boston, Massachusetts

Died 14 January 1928 in Boston, Massachusetts

Buried Mount Auburn Cemetery , Cambridge, Massachusetts

, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Proposed by Charles H. Haskins and Carl A. de Gersdorff

Elected 4 December 1915 at age forty-nine

Archivist’s Note: Brother of J. Randolph Coolidge; uncle of Archibald C. Coolidge

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

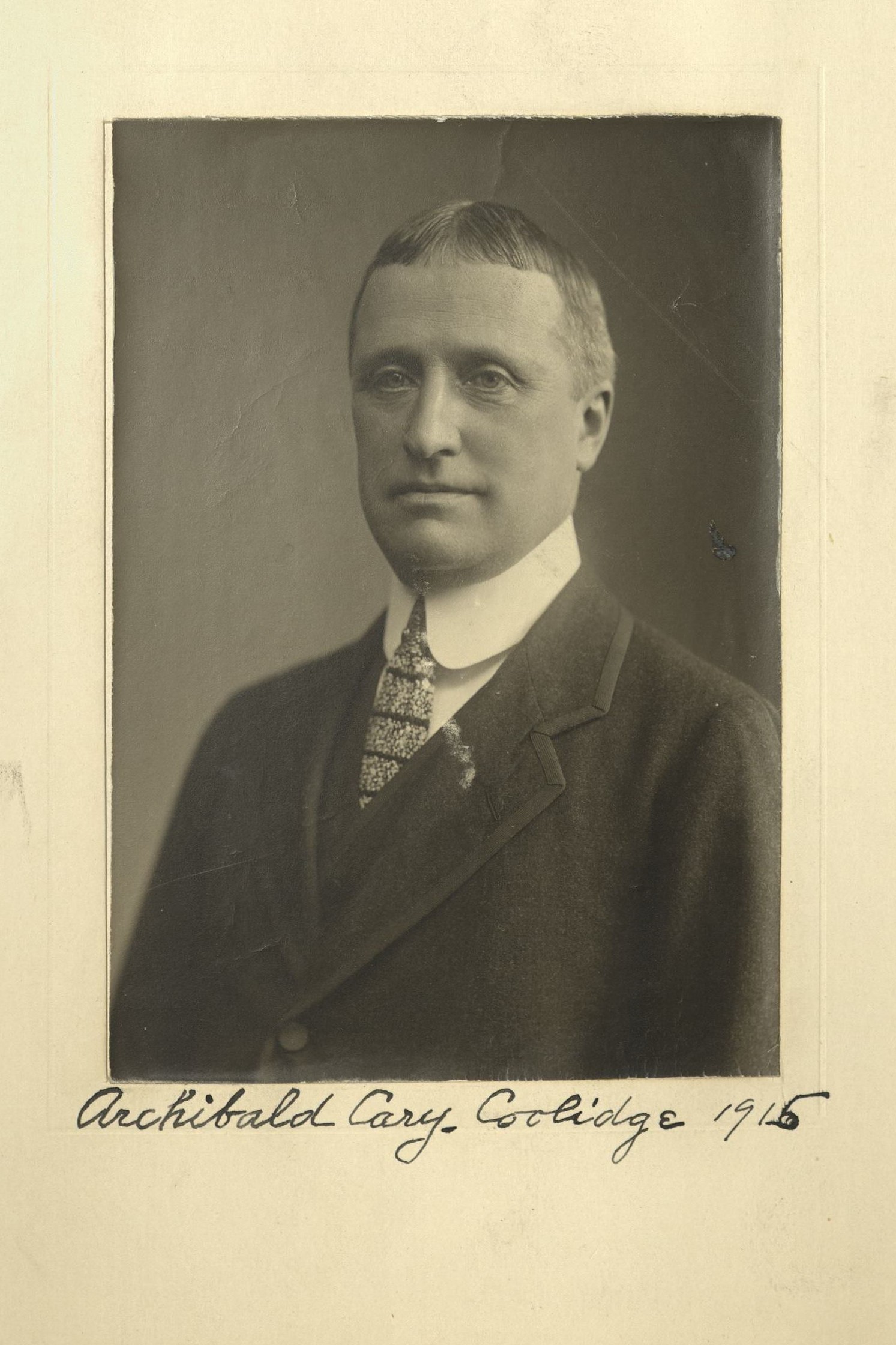

If he had not been a great teacher of history and international law, Archibald Cary Coolidge would almost inevitably have been a great diplomatist. The calling, indeed, belonged to him by inheritance; he was great-great-grandson of Thomas Jefferson and nephew of the American minister to France in the later eighties. He had seen actual service in the legations of Paris, St. Petersburg and Vienna and had done his part on the American staff at the Peace Conference. Individually, he possessed in unusual measure the qualities which are becoming increasingly indispensable in the diplomacy of today; clear and impartial understanding of political history, fearless judgment regarding the necessary consequences of a foreign country’s altered position in the family of nations, sympathetic insight into the underlying forces, often so elusive to the eye of a foreign observer, which create in it the great waves of public opinion and national sentiment.

Coolidge wrote and taught in the spirit of the new diplomacy. Poincaré said of a recent article by him on Franco-British relations that it was “the perfect type of historical writing” and that “no Frenchman or Englishman could possibly have done it.” But Coolidge’s view of his own country’s international relations was equally impartial. The United States of twenty years ago did not conceive of itself as a participant in the outside world’s affairs. The Spanish War had been an accident, the Philippines an encumbrance, Cuba more or less of a nuisance, the Monroe Doctrine nobody’s business but our own. But Coolidge wrote even in 1908 that in the larger world of which the United States was a part, its power for good or evil had become so great that the manner of using it was of consequence to all humanity, and that Americans might as well face the fact that “it is now too late for them to return to the simple life of their earlier history.” Unconsciously anticipating 1914 and 1917, he further hazarded the suggestion, in regard to Washington’s advice on “foreign entanglements,” that its indefinite observance “in our new period of world questions is open to doubt.” The wish to escape inconsistency in our own opposition to European intrusion into American affairs he considered one reason for our people’s anxiety to keep out of European questions. But “whether they will be able to do it is another matter.”

Why Coolidge should not, like Briand and Mazaryk and Wilson, have been drawn into the larger sphere of high diplomatic responsibility, it is difficult to say; perhaps his bent was stronger for instruction than for active participation in affairs. In his own work at Harvard he became known as a trainer of diplomats; in his humane and penetrating discussion of diplomatic questions during his editorship of “Foreign Affairs,” he held the balance of impartial criticism. The value of that kind of work by men of such calibre is very great, but the time may not be far distant when they will conduct our international relations.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1929 Century Association Yearbook